UC Davis Rolls Out Net-Zero Energy Housing Project

DAVIS, Calif. — The University of Davis, California will expand its net-zero energy portfolio with the debut of the West Village Boulevard Units to open in time for the 2013 school year. The seven-acre student housing development provides two-, three- and four-bedroom student housing configurations for 504 residents, as well as recreation areas and a pool.

DAVIS, Calif. — The University of Davis, California will expand its net-zero energy portfolio with the debut of the West Village Boulevard Units to open in time for the 2013 school year. The seven-acre student housing development provides two-, three- and four-bedroom student housing configurations for 504 residents, as well as recreation areas and a pool.

The Boulevard Units are part of the school’s 130-acre West Village mixed-use neighborhood, the largest net-zero energy development of its kind in the U.S. The first phase of the development opened in 2011 to about 800 students living in 315 apartments, but the community is estimated to eventually house about 4,200 residents.

Planning for the project started a decade ago to create new housing for a growing student population, but the net-zero energy concept was introduced well after the 2003 approval of the original plan. UC Davis West Village is designed to produce as much energy as it consumes in the course of a year.

“You have to drive down the energy need within your building first, which means you insulate it right, put windows in the right orientation and make them cross ventilate. You do all kinds of things to the building itself to reduce the need that a typical building would have,” said Eric Naslund, FAIA, of San Diego-based Studio E Architects, the design architect on the Boulevard Units project. “Once you do that, you meet that lower need with energy you generate on site, which in this case is all done through photovoltaic panels on roofs.”

San Diego-based Spurlock Poirier Landscape Architects served as the landscape architect on the project and contributed to the sustainability goal through the idea of capturing storm water to infiltrate the soil. “It’s not necessarily an energy savings as much as it is a sustainability quotient that improves the water quality,” said the firm’s Principal Martin Poirier. “Instead of the runoff water going into a storm drain and potentially getting polluted with surface contaminates, it’s captured and filtered in rock and soil filters.”

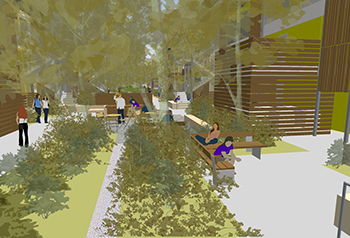

The central stormwater infiltration band also serves as a major design element for the project. The stormwater moves towards the infiltration band, and onlookers can see it go into a rock filter band that runs like a stream to the low point of the site while linking the landscape spaces such as intimate courtyards and the on-site fruit orchard. Another major part of the landscape design is the unified forest canopy made of native California trees indigenous to the Davis area.

Because the project was so environmentally conscious, a strict no-fly policy was enforced which posed as a challenge while also saving costs on transportation. This required the project team to use technologies such as video conferencing and live 3D models to collaborate without being on the job site.

“The merging of these technologies really does allow you to make design decisions remotely,” Poirier said. “Because technology allows us to model so specifically in 3D, then people can visualize in a much easier manner. We found it to be surprisingly effective and are even incorporating it into local projects so we’re not driving as much to meetings.”

Poirier said the biggest challenge was not being able to get instant feedback when the team monitored still images because they sometimes needed to see a different angle to make a decision. Not being on the job site, they had to wait for someone to get the needed photo for them. “There was a little more back and forth, but in terms of not having to fly, it was effective,” he said.

Apart from the net zero energy goal, another major design element was “making sure the community life was vibrant and connecting and made for a great neighborhood,” Naslund said. “Oftentimes, students are far from home, so making a place that is nurturing and connective and feels at home is really important to them.”

The design team created this connective environment by placing all of the doors to the students’ rooms on the building’s exterior. “Everyone walks to a door that’s outside. No one’s walking down an artificially lit hallway,” Poirier said.

A social element of the design is the six outdoor gathering spaces that each have a community table outfitted so students can bring meals and eat it from their room or cook food on community grills, Poirier said. “There was a high degree of attention to making these spaces really serve the needs of the students in their daily lives,” he said.