By Rachel Leber

BOULDER, Colo. — Professors Ronggui Yang and Xiaobo Yin of the University of Colorado (CU) in Boulder have invented a new passive cooling technology that has the potential to cool buildings without the use of power or electricity, and without the use of refrigerants. Their invention is a highly specialized film that uses the principles of “radiative cooling” for its function.

Professors Yin and Yang are currently a year and a half into what will be a three-year long project of developing their film and trying to figure out the best way to manufacture and market it. The funding for this project came from a U.S. federal grant for $3 million through the U.S. Department of Energy, according to Yin.

Their original idea for the invention was inspired by the work and discoveries of engineers at Stanford University in California in 2014. These Stanford engineers invented an ultrathin material that radiated infrared heat directly back toward space without warming the atmosphere. “With their invention, they brought to our attention the concept of these passive cooling concepts, and we started scratching our heads about possible approaches to lower cooling costs. It was inspiring for us because it is a passive cooling technology that could have a huge impact on our society,” said Yang.

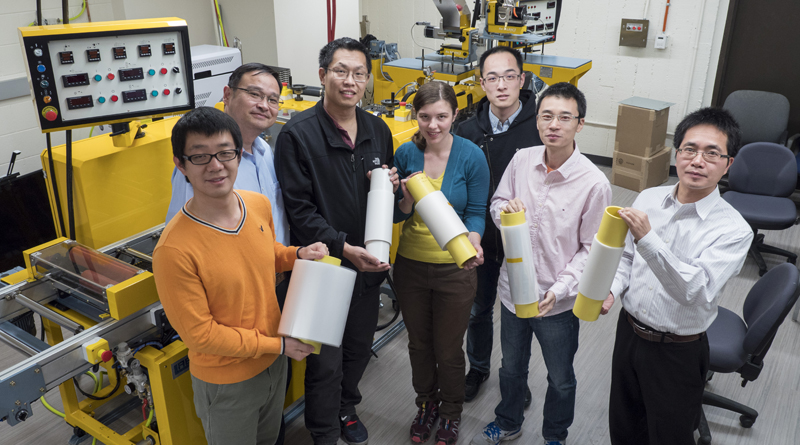

Efficient nighttime radiative cooling systems have been extensively investigated in the past, but daytime radiative cooling presents a different challenge, according to the professors, and is the challenge that Yin and Yang (and their team of five students and another CU professor) seek to meet with their new invention. The field of polymeric photonics is “a growing field attractive for economy and scalability,” according to their recent paper published in Science magazine, with other technologies created so far proving to be expensive and difficult to make on a larger scale.

The film that they created is comprised of extremely thin plastic sheets about 50 millionths of a meter (microns) thick, silvered on one side, with glass microspheres on the other. When these sheets are laid out on a roof or another surface like a solar panel, sunlight is reflected back through the plastic, which stops it from heating the building or surface below. The cooling effect of these glass microspheres is 93 watts per square meter in direct sunlight, and more at night, which is significant, according to a recent statement. The team estimates that 20 square meters of their film, placed on top of an average American house, would be enough to keep the internal temperature at 60-degrees Fahrenheit on a day when it was 98.6-degrees Fahrenheit outside.

Photo Credit (all): Glen Asakawa, University of Colorado Boulder

The CU professors’ film is made of polymethylpentene, which is a transparent plastic, mixed with tiny glass beads. Their film is less expensive and simpler to make than the original Stanford prototype, and thus more accessible to be used in a widespread manner, according to Yin. “Glass is a good material for cooling, and is actually pretty cheap and available,” according to Yin.

Questions the professors are currently investigating are, “How to best use the film?” and “How to best market and manufacture it?” There is also the issue of creating different prototypes based on the various possible uses of the film, whether it be working with homeowners, solar companies, large corporations and more, according to Yang.

“Nobody has tried to actively use these principles of outer space as an application to our problems here on earth yet. Now, we can utilize these principles without having to send a shuttle out into space, and instead put them onto people’s rooftops. I like to use the universe as a code for how we can solve our problems here on earth. It is inspiring to so many of us as engineers,” said Yang.